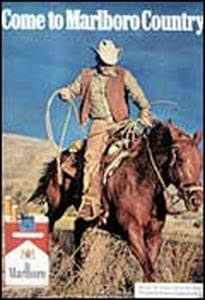

Since the late 1970s, when Richard Prince became known as a pioneer of appropriation art — photographing other photographs, usually from magazine ads, then enlarging and exhibiting them in galleries — the question has always hovered just outside the frames: What do the photographers who took the original pictures think of these pictures of their pictures, apotheosized into art but without their names anywhere in sight?

Recently a successful commercial photographer from Chicago named Jim Krantz was in New York and paid a quick visit to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, where Mr. Prince is having a well-regarded 30-year retrospective that continues through Jan. 9. But even before Mr. Krantz entered the museum’s spiral, he was stopped short by an image on a poster outside advertising the show, a rough-hewn close-up of a cowboy’s hat and outstretched arm.

Mr. Krantz knew it quite well. He had shot it in the late 1990s on a ranch in the small town of Albany, Tex., for a Marlboro advertisement. “Like anyone who knows his work,” Mr. Krantz said of his picture in a telephone interview, “it’s like seeing yourself in a mirror.” He did not investigate much further to see if any other photos hanging in the museum might be his own, but said of his visit that day, “When I left, I didn’t know if I should be proud, or if I looked like an idiot.”

When Mr. Prince started reshooting ads, first prosaic ones of fountain pens and furniture sets and then more traditionally striking ones like those for Marlboro, he said he was trying to get at something he could not get at by creating his own images. He once compared the effect to the funny way that “certain records sound better when someone on the radio station plays them, than when we’re home alone and play the same records ourselves.”

But he was not circumspect about what it meant or how it would be viewed. In a 1992 discussion at the Whitney Museum of American Art he said of rustling the Marlboro aesthetic: “No one was looking. This was a famous campaign. If you’re going to steal something, you know, you go to the bank.”

People might not have been looking at the time, when his art was not highly sought. But as his reputation and prices for his work rose steeply — one of the Marlboro pictures set an auction record for a photograph in 2005, selling for $1.2 million — they began to look, and Mr. Prince has spoken of receiving threats, some legal and some more physical in nature, from his unsuspecting lenders. He is said to have made a small payment in an out-of-court settlement with one photographer, Garry Gross, who took the original shot for one of Mr. Prince’s most notorious early borrowings, an image of a young unclothed Brooke Shields. (Mr. Prince declined to comment for this article, saying in an e-mail message only, “I never associated advertisements with having an author.”)

Mr. Krantz, who has shot ads for the United States Marine Corps and a long list of Fortune 500 companies including McDonald’s, Boeing and Federal Express, said he had no intention of seeking money from or suing Mr. Prince, whose borrowings seem to be protected by fair use exceptions to copyright law.

But with the exhibition now up at the Guggenheim — and the posters using his image on sale for $9.95 — he said he simply wanted viewers to know that “there are actually people behind these images, and I’m one of them.”

“I’m not a mean person, and I’m not a vindictive person,” he said. “I just want some recognition, and I want some understanding.”

Mr. Krantz, who retains the copyrights to most of his work, said he had been aware for several years that his work had been lifted by Mr. Prince, along with that of several other photographers who have shot Marlboro ads. But he said he did not think much about it, and said he had never talked with other Marlboro photographers about the issue.

“If imitation is a form of flattery, then I will accept the compliment,” he said.

But on one occasion a woman active in the art world visited his studio in Chicago, and, seeing a print of one of his pictures, Mr. Krantz recalled, “she said, ‘Oh, Richard Prince has a photograph just like that!’” And in 2003 Mr. Prince’s version of an image that Mr. Krantz shot for Marlboro — showing a mounted cowboy approaching a calf stranded in the snow — sold for $332,300 at Christie’s. Although the shot was blown up to heroic proportions, “there’s not a pixel, there’s not a grain that’s different,” he said. And so Mr. Krantz, whose Marlboro ads now appear mostly in Europe and Asia, began to grow angry.

He said that while he is primarily an advertising photographer, when he was growing up in Omaha, he did attend workshops with Ansel Adams. He studied graphic design and got into commercial photography, starting out in Omaha taking shots of toasters and pens and heating pads because that was where the work was. But he has long exhibited his own art photographs, recent examples of which show stark images of an empty prison as if seen through defaced or broken glass.

Mr. Krantz said he considered his ad work distinctive, not simply the kind of anonymous commercial imagery that he feels Mr. Prince considers it to be. “People hire me to do big American brands to help elevate their images to these kinds of iconic images,” he said.

He has considered trying to correspond with Mr. Prince to complain more directly but said he felt it would probably do no good.

“At this point it’s been done, and it’s out there,” he said. “My whole issue with this, truly, is attribution and recognition. It’s an unusual thing to see an artist who doesn’t create his own work, and I don’t understand the frenzy around it.”

He added: “If I italicized ‘Moby-Dick,’ then would it be my book? I don’t know. But I don’t think so.”